In the 1990s, the United Arab Emirates began experiencing a massive building boom known as the New Dubai. Projects like the Palm Islands, Burj Al Arab Hotel, Dubai Mall, and the most extravagant of all, the Burj Khalifa, became icons of an ever-changing city. The battle between architects, engineers, and designers commenced, each striving to leave a mark on the magnificent Dubai, offering architectural challenges that were both well and poorly received. From a city with strong traditional roots, Dubai transformed into a beacon of modernity and, some say, excess.

In fifty years, Dubai has undergone such a dramatic change and development that it has become unrecognizable. The urban built area exceeded 500 square kilometers, and the foundation for what would soon be the tallest building in the world was being laid. The construction of skyscrapers has lost its original purpose of being built in city centers that lacked space and required dense construction. Skyscrapers have become symbols of modernity and capitalism – when you have the power to go big, why limit yourself?

In the quest to establish its newfound modernity, Dubai sought to create iconic buildings to attract investors.

Anthropologist Kanna Ahmed writes in Dubai: the City as Corporation:

"Downtowns have transformed from contexts primarily for functional centrality to centers of symbolic capital. With the development of both information and design technologies, it has become possible to design increasingly radical and flamboyant (or “iconic”) buildings and to disseminate images of this photogenic architecture instantaneously on a global scale. Images of downtowns replete with aesthetically fanciful buildings, instantly consumable for their vividness and superficiality, are now standard implements in the advertising toolkit of both established major urban centers and, like Dubai, cities attempting to establish a cutting-edge reputation for themselves."

While considered "pointless," the Burj Khalifa has become Dubai's icon, polarizing everything.

Karmin Blair wrote for Architectural Record in 2010:

"Iconic skyscrapers, especially those that strive for the fleeting title of “world’s tallest building,” are rarely the progeny of cold logic. Their backers are invariably motivated by ambition and ego. The architect does not control whether or where such behemoths are built. He or she can only ensure that they are proud and soaring things, not Frankenstein-esque, XXL-size monstrosities. Such is the considerable achievement of Adrian Smith, FAIA, and his former colleagues at the Chicago office of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) in the gargantuan yet persuasive Burj Khalifa."

Its structure is an elegant creation of steel, concrete, and glass, designed to be graceful and refined, and to refocus attention away from the Palm Islands. Although the Burj Khalifa is not an exemplary model of green design, its double-pane low-E glass panels make up a skin system that traps condensation that would otherwise evaporate. While a small act for a building that will consume almost a million gallons of water a day in a region where water is a scarce resource, it nonetheless cuts back on water requirements by 20 percent.

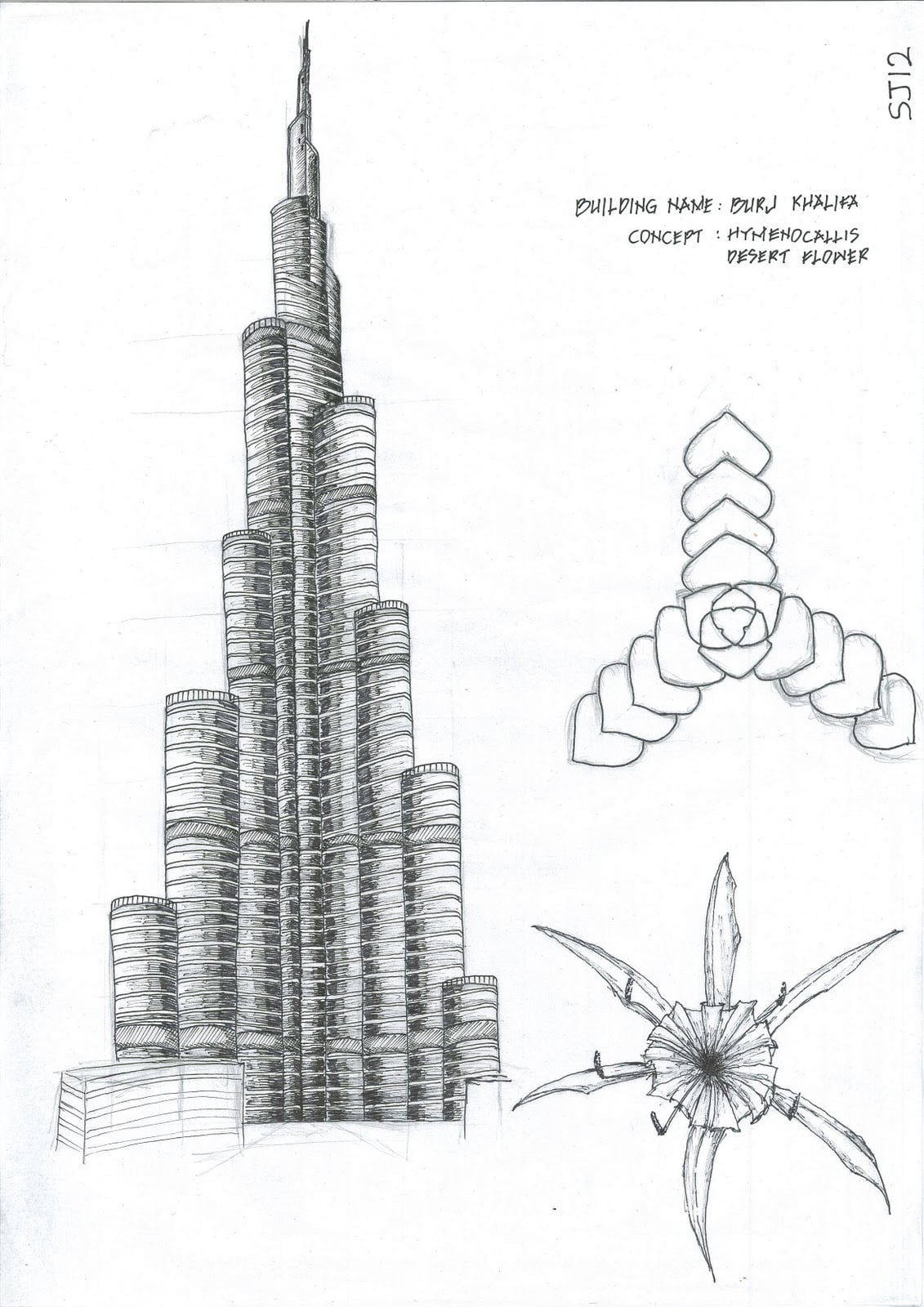

The Burj Khalifa's design spirals upward with a series of setbacks that gradually taper the tower to a slender end with a 700-foot spire. It was deliberately conceived to be more organic, partly due to an effort to echo local forms. The Hymenocallis blossom, a desert flower common in the Arabian Peninsula, inspired the tower’s triple-lobed footprint. The architects assert that the design contains motifs of Islamic art, and that when viewed from the base or the top, the tower “recalls the onion domes of Islamic architecture.”

Dubai’s rapid transformation had positive but also negative effects. The criticism continues, especially from the West, and it's ironic that the Burj Khalifa, and the entire Dubai for that matter would be criticized by the ones who designed and built it.

Rem Koolhaus writes:

“What has fascinated me in Dubai is how dominant our reading is. By “our” I mean the West. Dubai happened; we participated in its construction. We were complicit in its extravagance. But we were also the first to denounce its absurdity. What I fear, now that we have declared the “end-game,” is that we will also be the first to tell Dubai not to be itself anymore, to tell Dubai that it’s over and to declare prematurely an end, not only to an experiment, but also to a real cultural change that has been taking place in and underneath all of this, and that still deserves to reach its own conclusions.”

Related Articles

45 Of The Most Famous Buildings In The World With Unconventional Architectural Structures

5 Buildings Destroyed During WW2 Now Rebuilt From Ashes